Volume 054: Chet Doxas

THE VOICE OF ENERGY VOL. 054

Greetings, young lovers and all the ships at sea. I hope this finds you in a good way today.

Brass tacks time: starting in October, I'm going to be offering paid subscriptions for the newsletter. Only $5 / month to get a full meal weekly address from yours truly. There will be missives for folks that don't want to support (which I'm more than okay with) but those that do decide to chip in will get some additional treats.

The big one is that, each month, one lucky subscriber will receive a care package from me of a few vinyl LPs and some other goodies (zines, cassettes, t-shirts, the occasional CD). I'll work with the winner to make sure they're getting something they will want to spin, but trust me, these will be excellent and oft-overlooked gems that you'll be happy to have in your collection. More than likely used LPs in great condition but I may throw in the occasional new record as well. I'll be sure to send some info, written by me, on the selections to help put them in context. The caveat is that I will only do this if I get 20 subscribers. It would feel silly sending records to the same three people.

Even if I don't wind up offering care packages, I will definitely be soliciting exclusive mixes for your downloading pleasure from the many musicians, DJs, and music obsessives I know. Something to have in your arsenal for long drives or workouts. You'll love them, I promise.

I've got other subscriber-only ideas I'm still figuring out but I definitely want to feel like you're getting something special in return for your support.

Why do this now? I'm wearing of the freelance racket. The only outlets that pay well are most often run by corporate interests that I want no part of. With so many people scrambling for the crumbs that other spots offer up, it's also harder to get work, and to cover some of the lesser known artists and to go down the weird rabbit holes I want to explore. If I have you all backing me up, I might actually be able to spend some time digging into the Seattle Opera's 1971 performance of The Who's Tommy (with Bette Midler as the Acid Queen!).

This will mean more interviews, album reviews, film reviews, maybe some streaming suggestions, etc. I may start soliciting stories/reviews from other writers (for which they will be paid). I've got ideas percolating. I do believe it will be worth your while.

So, if you're willing and able, please consider a subscription. If you're already a subscriber, I believe you just need to pop over here and enter your email to unlock full access. And, seriously, no hard feelings if you can't do it. I love you just the same.

With that out of the way... let's get to the goods. See below for my interview with jazz saxophonist Chet Doxas about his new album and reviews of three recently released albums.

Chet Doxas

Imagine you're sitting in the back of a shuttle, heading to the airport one early morning, and you're sandwiched between Carla Bley and Steve Swallow, two of the architects of modern jazz. Then imagine, in the course of your sleepy conversation, Bley encourages you to start a trio, and they both instruct you to write one song per month over the course of a year. It's a directive akin to Miles Davis telling his then-guitarist John McLaughlin that it's time to start his own group: you heed the advice and follow it to the letter.

Which is exactly what saxophonist Chet Doxas did. He took 12 months to craft a new batch of material that would keep to the same instrumentation as Bley and Swallow's trio with Andy Sheppard—sax, bass, and piano—and then sought out two players that he could trust to get the scope of this project: pianist Ethan Iverson and bassist Thomas Morgan.

The album emerging from this framework and timeline, You Can't Take It With You (out on Sept 24 via Whirlwind Recordings) is a window seat on airplane at cruising altitude. The momentum is swift and gentle with plenty of open air, fluffy clouds, and colorful scenery to keep the mind engaged and at attention.

Doxas' resume is lengthy, including tenures with Dave Douglas, John Abercrombie, and Maria Schneider, but with Iverson and Morgan he may have found his finest collaborators. Iverson is at his understated best, using as few notes and chords as possible to harness the emotional core of each song. Listen to how he builds up the beginning of "The Last Pier" with gently splashing waves of melody or lets his solo on "Up There In The Woods" pop and sizzle. Morgan is perhaps even more minimalist, jabbing gently into the mix throughout as needed and tossing up surprise runs. That leaves all the room Doxas needs to be the music's finger painter, smearing and dribbling with brio and quiet determination.

That lot of mixed metaphors shouldn't distract from the simple truth that You Can't Take It With You is one of the best jazz records to be released this year and I was thrilled that Doxas agreed to let me ask him some questions, via email, about its creation.

You talk in the notes for this album about the directive you received from Carla Bley and Steve Swallow to compose one song a month. Is that an unusual practice for you? Do you usually work much quicker than that?

In the past, I've worked much faster than that. I would spend the time necessary to finish a song to the point where it was cogent enough to be playable and then possibly change it during or after the rehearsal process. It would probably take two or three two-hour writing sessions to complete a piece. When I was still living in Montreal (moved to NYC in 2014), I was doing quite a bit of commercial arranging for recording sessions (television, jingles, Cirque du Soleil, and even occasionally some large ensemble music). That was great training because you learn how to work fast, on the fly, and have to make everyone sound and feel good—like the composer, producer, sometimes director, and the other musicians in the room. While that training taught me a lot, I'm grateful to be able to work slower and spend more time on writing and arranging my own music. I look back on those times and think of all my favorite contemporary visual artists who were also draftsmen in their early careers and used those formative years to hone their craft and learn to work well with others.

If that's true that this forced you to slow down or take the full month to dial in each song, how was that for you? Did you enjoy the practice? Did it feel maddening at times?

I definitely enjoyed the process and can't imagine going back to any other way of working. I discovered that I like to work using something called the "Pomodoro" method (25 min work sessions with 5 min breaks). When the timer is going, I have a job to do and because of that the work takes on an observational quality. Sometimes I describe this job in terms of a marble sculptor's work: the sculptor starts with a slab of stone (blank sheet music), and begins to reveal the shape within the stone. One could say that that shape has always been there and that the sculptor is releasing the idea.

This also brings into question a larger topic that I find interesting: If the shape or sound has always been there and even if you are the one who puts pencil to paper to release it, does the work really belong to anyone? I like to think that it doesn't and that the act of exploring and discovering exists outside of the realm of ownership. I feel like I can hear this in my favorite musicians, see it in my favorite paintings, and am beginning to be able to recognize it in my favorite film director's work. But now I think I'm getting off topic.

Maddening? No. Testing? At times. Giving yourself permission to sit still and not do something is an important lesson to learn and I've learned this from my relationship with music. If the ideas don't come to me one day, I'm grateful for that time that I got to sit and feel stuck and I never leave my writing station during those 25 minute sessions.

Giving myself permission to take a month to complete a piece also affords me the time to edit. I find the editing process to be one of the most rewarding and soul searching parts of composing. I spent two weeks editing the piece "Twelve Foot Blues". You might not hear it because of its lean nature but trust me, I hacked away at that one until there was almost nothing left and then it finally made sense. That experience was like taking a two week long look in the mirror.

I tend to forget how much space that a drummer takes up in a jazz ensemble until I hear an album that doesn't feature a drummer. How was it for you to write music knowing that that rhythmic element wasn't going to be a factor?

It's funny because I was so concerned about each musician's individual tone in this group that I never "missed" anything. Ethan and Thomas have beautiful sounds and one of the ideas for this ensemble was to create and encourage a space where we could explore this combination of tones and see where we end up. Rhythmically speaking, everyone in the group is very aware, so instead of rhythm, I would say that I focused more on orchestration and let the rhythm serve the sound.

What can you tell me about how you landed on the collaborators that you chose for this project? Why did they make the cut over all your other available options?

Their tones and willingness to be playful. Ethan is a very expressive and dramatic player with one of the greatest piano sounds around. I appreciate that he takes the repertoire seriously but not himself. Thomas is an expert listener and responder. He is a bassist that improvises every note that he plays and I would say the same for Ethan. That is to say, sometimes bassists will rely on familiar patterns to fill out the sound. Thomas never does this, but instead holds himself to a very high standard of playing beautiful sounds in the moment.

So much of the music feels like it drew you into a real state of rumination, thinking on the artists that inspired you (Lester Young, Jim Hall) as well as your parents. Was that obvious to you from the start of this project?

Those names you have mentioned are always around me, along with Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Paul Bley, Jimmy Giuffre, Jan Garbarek, Miles Davis, Billy Hart, Michael Brecker, Ellery Eskelin and Arvo Part- and my peers and mentors with whom I get to regularly play: Jacob Sacks, Vinnie Sperrazza, Zack Lober, my brother Jim, and Michael Formanek. I'm glad that you hear the consideration in the music because that is how it feels to me as well. I'm grateful to be able to do what I do and I hope that the music represents this feeling.

You also talk in the press notes about the contributions of your wife and kids to the music, and how much their lives echoed through the work as you were writing. How was it to try and create this music with that going on? When you hear certain tracks or play them, does your mind's eye bring up certain moments involving them?

A lot of the music was worked after dinner time while my family was strewn about the living room reading, doing homework, catching up on mountains of paperwork (my wife is a physician). The interruptions in the writing process were always welcomed because life is full of them and I think it helped me be less precious about the work. I revel in the way that my family is part of this music and they add immense scope to my life each day.

What can you tell me about the artwork you made for the album cover?

I like to conceive of my own covers whenever I can. This piece was originally supposed to be an even larger anatomical heart model with lottery tickets glued on to it but when the heart model arrived in the mail I had to pivot. In the long run, I think that this version ended up being more successful and funny anyway. The obsession of wealth and physical appearance have reached a boiling point in our society, whose flames are only fanned by the advent of celebrity culture and social media. The piece on the cover is meant as a riff on the cosmic giggle of attachment issues and was created to poke fun at this uniquely human struggle. I was lucky to be able to work with the great photographer, Julien Capmeil, for this shoot. He just so happens to be my neighbor and surfing buddy.

What comes next for you? Any plans for the rest of the year and beyond?

Luckily, I am part of several projects that have and will be keeping me busy into the next three to four years and hopefully beyond. Throughout the pandemic, I got to know the bassist and composer Michael Formanek a lot better. Drummer, Vinnie Sperrazza, and I would make regular trips to his home and we would play in his backyard. These casual sessions developed into a more formal setting when Michael was awarded with composer's commission from the Jazz Coalition. He wrote a profound work called "The Palindrome Suite" and we are now known as the Michael Formanek Drome Trio. We have an album coming out in early 2022 with tour dates beginning in March and continuing through the summer.

I am also part of an ambient music duo called Larum with the electronic music producer, Micah Frank. We are currently in pre-production for an album of the music of Hildegard Von Bingen which will be released in late 2022.

I am also part of an ensemble called Landline whose music is composed in the style of the game broken telephone. Each band member creates an idea and emails it to the next one until all four composers have added to or edited the music as they see fit. In our live performance we collaborate with four visual artists who do the same thing. In between each of the four sets, the artists rotate to adjacent the canvas to continue painting as we play. The whole concept is inspired by the surrealist art game, exquisite corpse.

My brother Jim and I have a group together called The Doxas Brothers. We released an album earlier this year with Marc Copland and Adrian Vedady called The Circle and will be performing at Montreal's Off Festival in October as well as tour dates in the new year. And lastly, my ensemble Rich in Symbols will be releasing our second album in the new year. The music for this group is written in museums while I look at paintings. The paintings that I chose to compose for are from a group of Canadian World War I era artists known as The Group of Seven. I also included two other artists from this era in this series, Emily Carr and Tom Thomson. During the live shows the works are projected behind the ensemble as we play their corresponding pieces. Several of the aforementioned projects have accompanying videos on my website and YouTube page.

Album Reviews

Nala Sinephro: Space 1.8 (Warp)

Try as we might to comprehend the vastness of the space behind our pale blue dot, we still only capture a slice of it staring at the night sky or seeing panoramic pictures from the surface of another planet. That’s the feeling that Space 1.8, the debut album from London artist Nala Sinephro, evokes. The exploratory cosmic jazz on this dazzling full-length is merely the moon rocks and space dust from a much larger soundworld. “Space 3,” a clash of modular synth clouds and lightning strike drums from Sons of Kemet’s Eddie Wakili-Hick, is merely a minute and change taken from a three-hour improv session. And most of the songs on Space fade in and out as if it’s a transmission from a far off moon caught by a passing satellite. The result, though, is ideal for a young artist releasing their first collection of music: sparking in the listener a desire for more. Do the alien sax groans and harp glimmers on “Space 5” continue to transform beyond that song’s four minute snapshot? Would the horns, drones, and Geiger counter flutters on the cavernous closer “Space 8” take us to an even more ecstatic state? After the liquid groove and heated synth tones of “Space 6” evaporate, do they return as a downpour later on? The possibilities—much like Sinephro’s talent as a composer, producer, and performer—are limitless.

Lady Blackbird: Black Acid Soul (BMG)

Marley Monroe, the vocalist known as Lady Blackbird, is a tinder in search of a spark. The L.A.-based artist has apparently spent years in the trenches, working with a motley assortment of producers and artists (Christian rocker TobyMac, Tricky Stewart, Jam/Lewis) to find that right combination of sounds and mood to set her incredible voice alight. The hope was that writer/producer Chris Seefried would be the one to finally fan the flames. But Black Acid Soul plays it safe, containing Monroe when she should be running wild. She tries to find her way free throughout, soaring above the simmering cover of the James Gang’s “Collage” and flooding “Lost and Looking” with desperation and desire. The music, though, is missing that crucial x-factor. A touch of wildness or dissonance that would transform this album from a pleasant late night diversion or late afternoon jazz festival delight into something urgent and inescapable. Seefried and Monroe come the closest to this fire line on the title track, which closes the album. Cutting through the smoky rhythm comes the scraping of a bowed double bass and a watery, clipped melody played on what sounds like a rewired clavinet. If this is a precursor of things to come for this project, we’re in for something special on the next album.

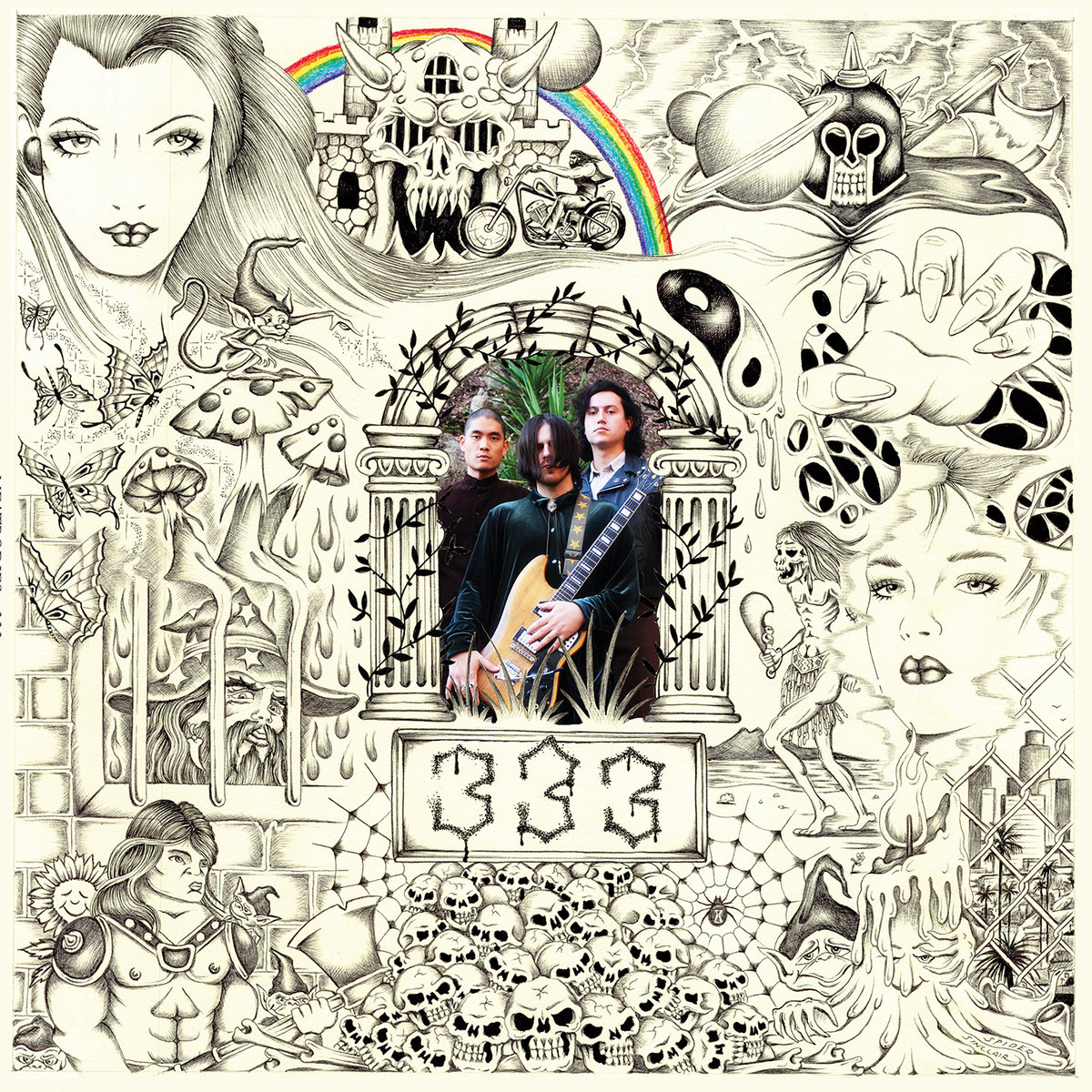

Meatbodies: 333 (In The Red)

The latest bundle of fuzz and gristle from this California trio is second only to Ryley Walker’s Course In Fable among this year’s expressions of rock bottom crashing and sober freedom. Lead Meatbody Chad Ubovich survived the torrid pace of his musical life (in addition to this project, he is a member of Fuzz and plays regularly with Ty Segall and Charlie Moothart) with a diet of drugs and alcohol for a number of years before hitting a moment of clarity. After steering away from disaster, he tapped into new creative vein and apparently already has a new Meatbodies record in the can. But before that can arrive, he cleared out the archives with this collection of buffed up demos from his period of recovery. Unlike Walker’s masterwork, it is much harder to pick apart the details of Ubovich’s struggles, as he seems more interested in vibes like capturing a “Expressway To Yr Skull” meets Isn’t Anything mood on “Eye Eraser,” tossing in a house beat at the end for good measure, or the Laurel Canyon burnout groove of “Let Go (333).” What pervades is the fascinating cognitive dissonance knowing that the deep Sabbath-grooves of “Reach For The Sunn” and “Cancer,” and the lava lamp melt of “Hybrid Feelings” would play perfectly under the influence of the right psychedelics. If it sounds this good when I’m stone cold sober…

That’s all for this week. Next time, my interview with Thalia Zedek, the Boston musician who has been a member of Live Skull and Come, and now fronts her own Thalia Zedek Band and the group known as E, and much more. Until then…

Artwork for this edition of the newsletter is from Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler’s new exhibition Flora, on display at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth through Jan 16, 2022.