Introductory Note to Chapter 5

I started this chapter maybe a few days before Halloween, and shelved it temporarily to take care of something, thinking I'd get back to it in a week. This, I sheepishly admit, did not happen as soon as I'd have liked it to.

What I was working on lay at the nexus of probably three separate decade-spanning threads of inquiry. My professional focus is, and has been for at least this long, about comprehension: helping people understand complex situations so they can make intelligent decisions and operate as a unit.

Now, I write documents and do slide presentations just like the next tech consultant, but I have had the growing impression, especially as the Web matures and we tuck into the early-mid 21st century, that the capabilities of digital media are still going miserably underutilized.

I have remarked in a number of places that if you take a garden-variety webpage and you shave off the navigation bar and the various insets, headers, footers etc., what you get is scarcely distinguishable from a Word document, which itself might as well be a printed piece of paper. Exceptions to this are mainly when the Web is being used as a delivery mechanism for software, rather than content. The latter is my source of interest, specifically dense hypermedia content, where traversing links—which themselves take many forms—is a major part of the experience.

When I say dense hypermedia, I mean it in contrast to sparse hypermedia, which is what we get with the Web as it is currently tooled: a lot of text and not a lot of links, and moreover a lot of things that could be links but aren't.

- Hiving off details, digressions, parentheticals: hypermedia (text or otherwise) could be unparalleled in its ability to get to the point. When you write an ordinary document, you have to include all this ancillary information inline: em-dash asides, parentheses, insets, marginalia, footnotes, endnotes, and so on. Making this content optional means busy people don't have to read any more than they need to.

- Providing background information: the same mechanism used to abridge digressive details also works to discreetly help the reader get up to speed if they aren't familiar with some aspect the subject matter—say a particular concept, term, or entity. No need to be seen asking “dumb questions”.

- Reusing content: not just to save time, but to avoid creating duplicates, ensuring all referring documents remain accurate when said reused content is updated.

- Mixing media: something the Web is already pretty good at: integrating text, graphics, audiovisual, and interactive elements. Although…

- Providing computable representations of structured data: mixing media, especially interactive visualizations, depends on data that can be used directly by the computer without any additional (human-powered) formatting or interpretation. Structured data may be represented in a table, record set, or chart for human consumption, but without formal structure and labels, it can't be repurposed for computation. We solve this by generating variants—ways of asking for the same content in a different container—and by embedding this formal structure into the documents themselves.

When I made a new website in 2007-2008 (after not having one since around 2002), I was determined to write it under a “proto” dense-hypermedia paradigm (I hadn't yet come up with the term): short documents, never more than a screen worth of content, completely stuffed with links—every thought gets its own page. This, it turns out, is really hard, so I eventually gave up and started writing ordinary essays—apparently hundreds of them.

The problems I was running into at the time reduce to the fact that the overhead of managing the hypertext got in the way of actually writing it. Specifically:

- If I wanted to link to something that didn't exist yet, I had to stop and think up a URL for it. Now, wikis handle this, but they do it badly, as URL naming is consequential, and half the reason for so much link rot on the Web is people renaming them willy-nilly.

- Then, I had to create a stub document so there was something to link to. Or otherwise, disable the inbound links so there is no route to a nonexistent or otherwise unfinished document. Again wikis do handle this, but also badly. The real problem here though was just keeping track of the stubs that I had started but not yet finished.

- The surface area of hypertext is surreptitiously huge. I would set out to write something without the faintest sense of how much effort it would take, in part due to raw overhead, but mainly because there's an invisible dimension that absorbs all your effort.

Conventional documents are simultaneously bigger and smaller—or, perhaps, thinner—than comparable hypertext networks. Due to the constraint that all parts of an essay, for example, have to show up on the page, it has a relatively well-defined scope. Hypermedia, by contrast, has an infinite number of nooks and crannies in which to sock away more stuff. It is actually reasonable to expect the amount of work involved in any hyperdocument to be proportional to the square of a comparable ordinary text. The formal reason has to do with graph theory, but the intuition is that there's another dimension that we can't see when we're looking at a document—itself strictly-speaking a one-dimensional object—because we're looking “down” at that second dimension edgewise.

In the last 15 years, I have developed techniques and tools that solved the bulk of the aforementioned problems, with the ultimate aim of returning to the dense hypermedia question. Outside of a few specialized engagements, though, I did not tackle it head-on until late 2022. (I had one of those “if not now, when” moments.) Remarks:

- Content reuse is essential, if for no other reason than a big chunk of linkable content can and absolutely should be reused. It's a whole universe of extra work otherwise, and a wild one at that. Microcontent and metadata is individually small enough to deem it not worth the candle to look up instead of writing anew, but (especially since it is linked together too) adds up to a formidable time suck. I spent about a week and a half just consolidating a bunch of duplicates I had generated over the last five years or so, a debt that had finally come time to repay.

- The tooling and infrastructure I had written got quite a workout. In some cases it was because there was a particular effect I wanted to achieve that I hadn't previously anticipated in the tooling, in others because I was trying to fit together parts that hadn't previously been put together, and others still because of reconciling changes with third parties. As I wrote elsewhere, I probably stepped on every rake in the system, but the good news is, I'm now out of rakes.

- There is all sorts of hidden work in the final presentation. Once you create all the parts and gather them up, it might not be immediately obvious how to arrange them. You will need time to do a final curatorial packaging of the artifact. This could be palliated somewhat by establishing a set of archetypal hypermedia artifacts, but those archetypes are only going to be identified by stumbling around in the dark.

- I'm actually inclined to say that the logic of

deliverable = artifact is anathema to the spirit of hypertext. It costs asymptotically nothing to add a single connection or piece of content to a hypermedia network, such that to cut all that activity off because the product is “done” seems like a bad idea. While there should perhaps be checkpoints of “done-ishness”, these artifacts (if we can call them unitary artifacts) should never really be considered fully “finished”.

The way I did this dense hypermedia project—and the wisdom of this is still debatable—was to write out the full-length document, and then start bucking it up, separating it into gloss versus details. There is also a completely stripped-down, structured version of the rationale itself, which is linked throughout the document(s).

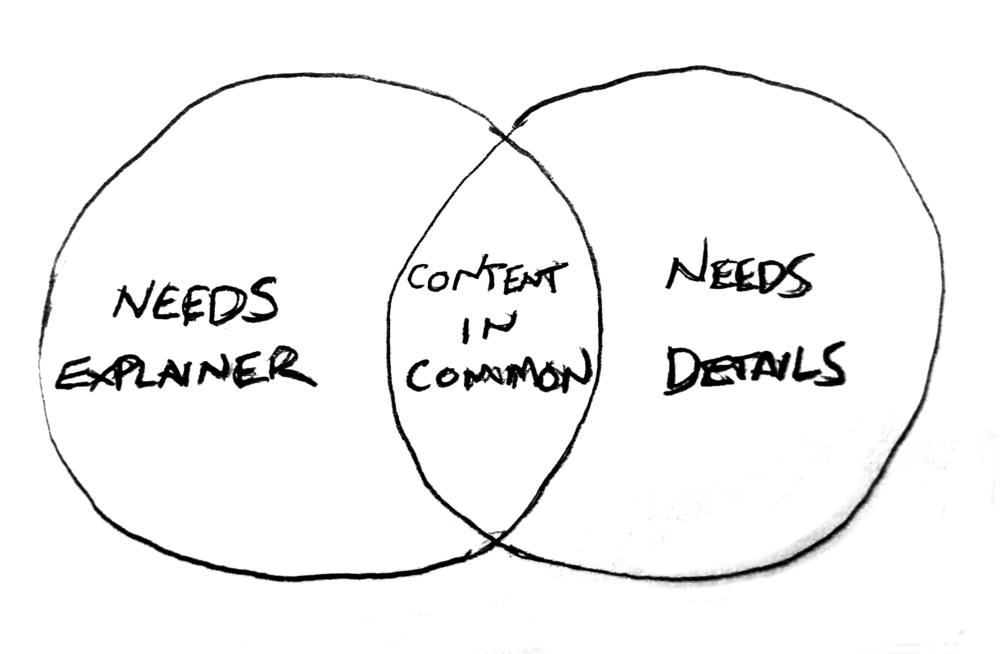

What I have found in my career—and what ultimately motivated me into this line of inquiry—is that technically-inclined readers insist on details that cause the rest of the population—which includes business leaders—to bristle. What little technical discussion you absolutely cannot scrub away is going to have to be nerfed with a like-I'm-five explanation of what the detail is, and why I insist on bothering you with it. The technical people will naturally find this boring and remedial. You just can't reconcile these two audiences with the same document, but you should be able to with a hyperdocument, even if it's just to share content common to both audiences without having to make a duplicate copy of it.

What does this mean for you, a Nature of Software subscriber?

- Well, for one, the resumption of a monthly publishing schedule, as the thing that has been eating my waking life for the last several weeks is now done, and monthly seems to be what I can ordinarily manage.

- But more importantly, since I just ironed out the kinks on a whackload of new capability, I'm setting up a second archive on

the.natureof.software where I'm going to put augmented versions of published chapters and other resources, to which all subscribers will have access.

This project is, at root, an attempt to make Christopher Alexander's The Nature of Order relevant to software development, while at the same time abridging the reading task by an order of magnitude. This is still on track. Indeed, I suspect that part of the reason for friction around the uptake of Alexander's ideas is that there is just so damn much material to read. While the main artifact here will still be a book-like thing serialized as a newsletter, there is still plenty of opportunity to both compress and enrich the message even more. Alexander's work is furthermore full of concepts and processes that can be spun out as structured data to remix and build upon.

In general I endeavour to move into the hypermedia space and live there permanently, such that conventional documents like the one you're reading are projections of higher-dimensional structures, flattened and desiccated for less dynamic media. The newsletter will continue, of course, but it will be a snapshot of what's happening online. That's the goal, at least.

At the time of this writing, there is nothing on the.natureof.software, because I just bought it. There are a few things I need to do before I have something minimally viable up there, like setting something up to sync accounts, and making an index page. Then I can work on certain data products like a concept scheme (the bulk of which I have almost certainly written down elsewhere), and interactive capabilities like collaborative annotation. Definitely by next issue there will be something there to log into.

And now, enjoy Chapter 5 of The Nature of Software: Positive Space.