the compagnon’s staircase

the compagnon's staircase

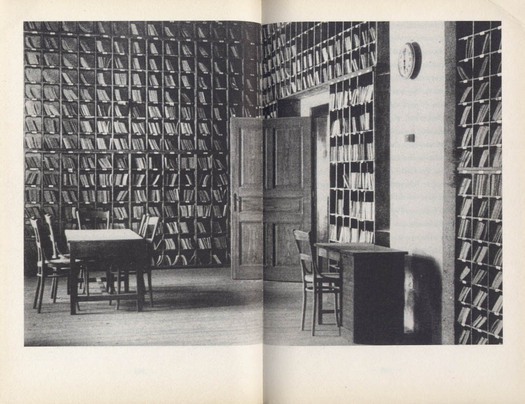

Niklas Luhmann always worked with a collaborator, whom he scrupulously credited: his Zettelkasten, a slip-box of pieces of paper on which he summarized ideas. The almost 90,000 slips, housed in cabinets of long, sliding drawers, was not just a collection of citations or research materials, but an extruded version of Luhmann's own thought process and his capital-S System philosophy of society, and an indirect biography. (In fact it is two collections of slips, reflecting a fundamental shift in his life and work, narrowing towards the questions that perplexed him; the first collection had 108 topics, the second had 11.) Gathering and assembling slips was how he wrote; following the associations between slips in the act of gathering them was, for him, a process of discovery, meditation, and surprise. These associations -- the connections between things -- were made possible through his finding scheme: each slip was an idea, a note, with a number in the upper right-hand corner. Note 1,1 is the first note of the first collection (which was Luhmann's way of roughly dividing by topic; the first collection of his second Zettelkasten was "Organizational Theory"). Note 1,1a is about something that refers to the idea in 1,1. 1,1b continues the thought from 1,1a. 1,1b1 branches off from the idea in 1,1b, and 1,1b2 continues that thought. In practice, over decades, this yields slip addresses like 21/3a1p5c4fB1a ("Confidentiality") and 21/3d26g53 (for the ideas of his nemesis Jürgen Habermas).

Every slip, as he wrote it, would include the addresses of other cards with which he felt it was connected, and in working his way back and forth through the network of slips he would add new connections to old cards. An additional thought or reading or discovery about an old idea could be inserted into the collection (branching off into 1,1b1a); the slip-box could expand more or less infinitely internally, as interlinked connections grew denser and ideas branched off in new directions or rolled on in consecutive digits. Quite the opposite of a neatly shelfmarked hierarchy of knowledge, where every notion has its eternal place, Luhmann's cabinets were a compost heap in need of regular pitchforking. In the Zettelkasten itself, he compared it to a cow's multi-chambered stomach ("Verdauungssystem eines Wiederkäuers," 9/8i) -- a constant process of cud-chewing, but without excretion. Luhmann would revise, but never discard, with slips devoted to mistakes and dead ends linking to their own corrections.

Luhmann talked about his slip-box system often, crediting it with his remarkable productivity (the hundreds of articles, the dozens and dozens of books) and his capacity to write incrementally, setting down one project at the moment it became difficult and taking up another, since all of them existed in embryonic form and outline in the chain of slips -- it was just a question of writing the connections from one note to the next. Rather than a project-specific collection of notecards, like Gershom Scholem’s cards for words in the Zohar, or the citations of use for the Oxford English Dictionary, the Zettelkasten contained all the possible future projects Luhmann might write, their connective tissue waiting to be discovered. (Luhmann described the goal of the Zettelkasten: to "maintain openness toward the future," 9/8h.)

What makes it especially interesting to me (aside from the devotional, meticulous excess of the thing) is that it is built around Luhmann's fundamental, atomic unit: the concept. The slips carry summaries and explanations of concepts, examples of concepts, consequences of concepts: sovereignty, class, formal order, equality, information. Writing, for Luhmann, is about linking ideas together.

Wittgenstein also had Zettel, slips of paper on which he would write sentences and remarks -- hundreds of slips which he stored in a safe, no less, alongside the canvas beach chairs and card table that constituted almost all the furniture of his Cambridge rooms. Part of his thinking, writing, and teaching all involved taking out one or a handful of those slips and discussing their paradoxes and challenges. For Wittgenstein, the unit of work was the sentence, or a few sentences in a paragraph: written in a pocket notebook, selected from the notebook to be typed up, cut into slips from the typewritten pages, arranged and rearranged, added to and further transformed. "Each of the sentences I write is trying to say the whole thing, i.e. the same thing over and over again; it is as though they were all simply views of one object seen from different angles."

For Walter Benjamin it was the quote, written in his notebook registers and card files and beautiful notation symbols for weaving together the vast tapestry of Belle Epoque Paris for the Arcades Project (categories of the convolutes: "Idleness," "Modes of Lighting," "Hausmannization, Barricade Fighting," "Marx," "Boredom, Eternal Return" ...). The quotes were the matter to be assembled, rearranged, juxtaposed, and montaged — the unit of work.

W.G. Sebald was the starting point for all this. I've been rereading Austerlitz and The Rings of Saturn and The Emigrants and trying to understand how they work so beautifully -- with such craft that you are carried along through so many interlaced events, places, and histories without ever noticing the joins and seams. I think Sebald's unit of work is the recounted memory: the handoffs between sections of his stories are transitions from one memory, recalled and recited, to another -- whether contained within it or reminding the speaker of something else. The book works, in some ways, by how it puts together recounted memories. In what order? What nests within what? What brings the next recollection up? And what is being forgotten, or sidestepped, or ignored (for now)?

The concept, the sentence, the quote, the recounted memory. In the craft tradition of compagnonnage, the apprentice proves themselves through the production of a single work that contains within it all the skills they have mastered. The carpenter compagnons would create an exquisitely detailed miniature staircase, demanding joinery, marquetry, inlay, and fluency with every sort of woodworking tool. (Sarah Coffin's wonderful book Made to Scale is the resource on this flower of craft.) It was the smallest possible thing that contained all the rest of one's work: all the possibilities of what one could make, expressed in a single object.

theme

Moondog, Theme (Instrumental) off the self-titled album from 1969: music for the starting point and the first step.