Having Better Conversations About Race

A climate scientist prepares us for hard conversations about racial justice... just in time for those awkward holiday gatherings.

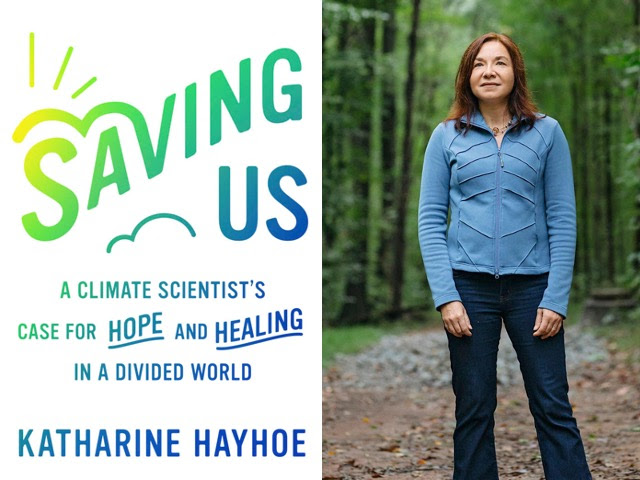

The best book about racial justice I've read this year isn't about racial justice at all; it's about climate change. More precisely, Saving Us is about how to talk about climate change with people who aren't all that interested in talking about climate change.

Some of us are looking forward to visiting family and friends next week, maybe for the first time in a long time. As is often the case when people who don't regularly see each other gather around a table piled high with food and drink, it's likely that some interesting conversations may present themselves. In fact, one of the requests I most often hear made of white people by our friends of color is that we would show up to these tables ready for challenging conversations. After all, it's one thing to speak up for racial justice when surrounded by like-minded friends but the real test of our solidarity shows up around Thanksgiving tables and Christmas trees.

Dr. Katharine Hayhoe is a leading atmospheric scientist and the Chief Scientist for The Nature Conservancy. She's also a Christian. In Saving Us she points out that "climate change used to be a respectably bipartisan issue." It's only been within the past ten years that polarization has set the tone for how we talk - or don't - about climate change. This observation reminded me of some recent conversations with pastors. Many of these clergy feel as though the ground has shifted beneath their feet and that the biblical themes of unity and justice they could previously preach and teach about are now fraught with partisan tension. This isn't to say that churches, white churches especially, have a good track record when it comes to these subjects, just that those who have been willing to engage are finding their task increasingly difficult.

Hayhoe wants us to look more closely at this polarization. While some paint the so-called climate deniers with a broad brush, she sees a more nuanced spectrum from the most concerned about climate change to the least. All of these groups, she points out, can be engaged with. For each there are effective ways to begin the conversation about what we can do about a changing climate. It's only at the the farthest end of the spectrum that we find those who are totally dismissive of climate change. "A Dismissive is someone who will discount any and every thing that might show climate change is real, humans are responsible, the impacts are serious, and we need to act now. In pursuit of that goal, they will dismiss hundreds of scientific experts, thousands of peer-reviewed scientific studies, tens of thousands of pages of scientific reports, and two hundred years of science itself." And while the Dismissives "dominate the comment section of online articles and the op-ed pages of the local newspaper," they only make up 7% of the population. Hayhoe's advice? Ignore the seven-percenters; they are purposefully antagonistic and derive core parts of their identity from their denials.

The good news is that this leaves 93% of people available to talk with about climate change. That's a lot of people! The connections for those of us pursuing racial justice are obvious. I sometimes get asked about how to engage with people who deny the existence of racism or who become hostile when the topic is raised. My advice: don't waste your time trying to reach that person. Partly this has to do with how Dismissives are unlikely to change their minds, but mostly I'm thinking about the many people who are open. By refusing to get sucked into endless debates with a small percentage of people we can pay attention to all of the people who, while not actively advocating for justice, are at least open to learning and growing.

And how do we engage with all of those people? This is where Hayhoe is especially brilliant. Most of the book is packed with ideas and anecdotes about having good conversations about the polarizing topic of climate change. She begins by suggesting that difficult conversations should start with the values we share in common. These values might include the places we live, the things we love to do, the people we love, and what we believe. Take that last one for example. "If Christians truly believe," writes Hayhoe, "we've been given responsibility - "dominion" - over every living thing on this planet, as it says at the very beginning of Genesis, then we won't only objectively care about climate change. We will be at the front of the line demanding action because it's our God-given responsibility to do so. Failing to care about climate change is a failure to love. What is more Christian than to be good stewards of the planet and love our global neighbor as ourselves?" Rather than starting with data and facts, the key is to move from "who we are to why we care."

So, why do you care about racial justice? For some of us the answer is obvious- our lives are visibly devastated by racism and white supremacy. For others of us though, the answer is less blatant. If you are white, how do you talk about why justice and reconciliation matters to you? How do talk about justice so that it intersects with the values of your conversation partner?

If we're not thoughtful about these shared values, our conversations can quickly tip toward fear and guilt. When our conversation partners begin to feel either of these emotions, they begin to suspect that we simply want to win a debate or are trying to prove our moral superiority. Whatever the response, the conversation is stopped cold in its tracks. Now people feel like they have to defend themselves, oftentimes by attacking your motives.

To avoid these common conversational pitfalls, Hayhoe makes three suggestions. First, we need to understand the reality we're describing. It's important to be able to describe why climate change - or systemic racism - should be deeply worrying to everyone. For example, what will you say when your uncle, wiping the crumbs from his lips after dinner on Thursday, opines that the verdict from Kenosha yesterday had nothing to do with race? Second, while accurate information is important, we also need to be ready to talk about how we can make a positive impact. We are wired for solutions and forward movement. Be ready to articulate to your conversation partners why we need their participation in the struggle against injustice. Finally, to counteract guilt and fear, we need to be able to offer a redemptive pathway forward. Here Hayhoe sounds a bit like a preacher. "So how do we move beyond fear or shame? By acting from love." It is our love for those whose minds we hope to change which allows us to share a hopeful vision which includes them. And once a person can imagine themselves in that hopeful future - a future where the climate has stabilized, where justice rolls down - they might be willing to take steps toward that future.

I've barely scratched the surface of all this book has to offer those who regularly find themselves in difficult conversations. To those of us tempted to opt out, to surround ourselves with people who already agree with us about racial justice (or climate change), Saving Us is challenge and a roadmap. Don't bail now! The stakes are too high. There are creative and productive ways to have these conversations. This is especially true for those of us who are white. Remember please, our friends and colleagues of color don't have the option to step away from this stuff. Refusing to walk away can be an act of loving solidarity. And as long as we're going to have them, lets learn to have these difficult conversations really well.

(Photo credit: cottonbro.)